Sample Chapter

Chapter 5:

Do not pull the bamboo pole!

In the previous chapter I discussed the transition of Disneyland, in the later years of Walt’s oversight, towards the creation and focus on larger, E-Ticket spectacles – resulting in greater quality and larger, but overall fewer, attractions. The primary problem potentially posed by this strategy is the problem that plagues Disneyland, and the other Disney parks around the world, to this day: overcrowding. With fewer rides, even if they are spectacles that draw people from around the world, won’t those rides be clogged up with crowds of people?

Even 60 years after its opening, Disneyland still draws crowds large enough to breach its capacity. As I described in the first chapter, on my trip to Disneyland for the 4th of July, 2015, the park was so overcrowded that I couldn’t stand anywhere on Main Street or in the central plaza (often referred to by cast members as “The Hub”) without touching other people. Looking at reviews of the park online, it seems the single most prohibitive factor in embarking on a trip to Disneyland is the crowds.

The crowds have become a problem to such a degree that Disney has recently introduced seasonal pricing at its parks in California and Florida, as well as raising the prices overall, in an attempt to discourage visitors from going to the parks, spending money, and generating profit for the company, at the park’s peak times.i If a company is willing to potentially loose revenue to solve a problem, you know that the problem is a big one.

While overcrowding – which we can see manifest through increased waits, and overflowing lines – is perhaps the biggest problem which has spread throughout the Disney theme parks around the world, some of the older rides – those very E-ticket spectacles built during Walt’s last years directing the park – are less subject to these problems than many of the newer rides in the park. Walt and the original Imagineers at WED Enterprises conjured up 2 main (ingenious) ways of dealing with overcrowding that I’ll get to in this book.

This chapter visits one of these measures, which was developed much later than the other. In fact, this was arguably one of the last feats of the original Walt-directed Imagineering crew, coming to fully blossom only after Walt’s death. The strategy was not present in the snaking, simple metal queue lines of the Matterhorn, Submarine Voyage, or Monorail, brought to Disneyland in the 1959 expansion (directed by Walt). It was not even present in the looping garden-enclosed queue line of “it’s a small world”, developed for the 1964/65 New York World’s Fair and brought back to Disneyland in 1966 (also directed by Walt).

Pirates of the Caribbean was the first ride which pushed the preconceived boundary, and asked the question (with it’s talking parrot display), “Why does the show have to start in the ride?” Pirates of the Caribbean was the first ride in which the experience bled out of the show building – the experience started in the queue.

In the queue of the Matterhorn Bobsleds, for instance, you, as a guest, simply wait in line for your turn to ride the bobsled. The ‘experience’ of the ride – careening through the alpine slopes – doesn’t start until you’re in the bobsleds, buckled up, driven slightly down for your final safety check, and finally whisked up onto the first chain-hill. Only then are you inside the mountain, riding your bobsled unhindered, and thrust into the storyline of the attraction: (which, since 1978 has been) a yeti chasing you.

Conversely, in Pirates of the Caribbean the ‘experience’ begins once you’ve made your way through the section of the queue positioned outside; as soon as you reach the inside of the facade, you’re greeted by a parrot audio-animatronic – beckoning you with pirate jargon – and a pirate’s treasure map. After a few more steps, the brickwork, plaster walls, and wrought iron fencing of New Orleans Square fade away as you are introduced to Laffite’s Landing, where you can see inside the Blue Bayou show building – all before you’ve exited the queue. Before you’ve even exited the line, the show has already begun; you have already embarked upon the storyline of being a pirate.

While this measure doesn’t necessarily cut down on the time waited until a guest can board a ride vehicle, it cuts down on the time that guests feel like they’re waiting – which is all that matters.

Unlike some of the other principles that I believe Walt was building to, this idea has not been forgotten or left by the wayside by the Imagineers. This technique – of starting the story before the line ends – has been attempted in several recent attractions. Today, many imagineers even refer to the queue of the attraction as ‘Scene 0’.ii

However, some of these recent attempts have faltered. In Buzz Lightyear’s Astro Blasters, in Tomorrowland, a person-size Buzz Lightyear animatronic briefs you – a new ‘Space Ranger’ – on the details of your mission before you board your spaceship (ride vehicle). Even though the Buzz Lightyear animatronic serves to start the story before the line is over, the rest of the queue has a cheap feel, composed mostly of flat murals which do not have animated or interactive components. The ride employs Disney’s Omnimover system, allowing the ride vehicles to be continuously in motion by loading guests from a moving ramp (this technology is also used in rides like the Haunted Mansion and The Little Mermaid ~ Ariel’s Undersea Voyage). Due to the positioning of the Buzz animatronic so close to the Omnimover loading platform, in combination with the circumference of the queue around the Buzz animatronic, passengers are moved too quickly through too small of a space to hear the entirety of Buzz’s speech, fully briefing them. Nearly every time I stand in line for the attraction, I have to run past the animatronic, barely hearing what he’s saying, in order to keep pace with the rest of the line. Placing the Buzz animatronic in another orientation (in respect to the queue line) would have resulted in more guests being able to hear more of Buzz’s speech, and therefore a more thoroughly integrated queue-ride story.

Star Tours also features this technique, using animatronics of C3PO, R2D2, Admiral Ackbar, and various original security droid characters, as well Departure / Arrival boards, screens, and safety warnings like those seen at airports to add a level of interactivity and a continuation of the story to the queue. However, I often feel as though I am waiting in line for the ride, even when in this section of the queue – probably because the experience it’s trying to replicate is waiting in line, but for an airplane rather than a spaceship.

While these recent queues could have removed the feeling of waiting further than they did, some of the ‘standout’ attractions, wherein this principle of starting the story in the line is applied very successfully, are also recent. Indiana Jones Adventure took a negative feature influencing its development – posed by the lack of space in the park, and the resultant construction of the show building of the attraction nearly a half a mile away from the entrance to the attractioniii – and turned it into one of the best-themed lines in any Disney park today.

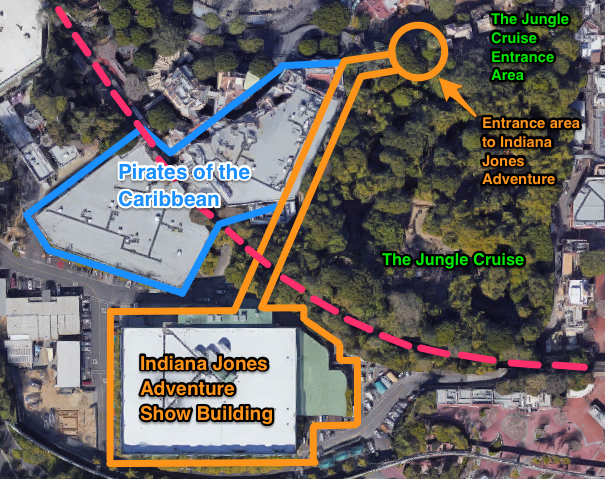

The image in Fig. 5, taken from Google Earth, is annotated to show the size covered by the Indiana Jones Adventure Queue Line. Fixtures of Indiana Jones Adventure are shown in orange, and for reference, are compared with Pirates of the Caribbean (labelled in blue), fixtures of the Jungle Cruise (labelled in green), and the superimposed path of the Disneyland Railroad, also marking the boundaries of the park’s berm (labelled using the pink dotted line). The Indiana Jones Adventure show building is outside the boundaries of the park’s berm; this is also the case with the New Orleans Square attractions. Like the stretching portrait chamber in the Haunted Mansion, and the drops at the beginning of Pirates of the Caribbean, the length and downward slope of the Indiana Jones Adventure queue serves to connect the entrance area of the attraction with the show building, and to take guests underneath the tracks of the Disneyland Railroad to get there. The orange connection between the Entrance Area and Show Building of Indiana Jones Adventure shows the approximate area of the queue.

Practically every inch of that half-mile is themed, taking guests not just through the Temple of the Forbidden Eye, but, more importantly, through the story of Indiana Jones’ adventure there. Old looking news reels are shown, this time in a room with snaking lines, giving guests the opportunity to often see the entire reel. The queue railings themselves are even themed to look like bamboo crafted scaffolding, set up to accommodate visitors looking for treasure, like you. The walls are littered with messages in another language, resembling hieroglyphics, that you can actually decode (legends showing the inscriptions’ english equivalent used to be handed out at the ‘Trading Post’ gift shop across from the entrance to the queue – today you can find copies of the decoder online).iv Detailed prop staging shows the booby traps that Jones had to circumvent to enter the temple. Interactive effects even bring some of the booby traps to life – albeit rarely, due to frequent technical difficulties. For instance, the splintery-looking bamboo pole holding up a spiked-laden ceiling, sprinkled on the sides with human skulls: the bamboo pole is made out of a flexible material, and, when pulled, triggers a slight drop in the ceiling, as well as sound effects, which give the impression that the spike chamber is closing in on you and your party, claiming its next victims. This effect in particular rarely works (although it did for the first time in years – that I had been there for it anyway – on my birthday in 2016!).

Even in the outdoor area of the queue, broken down trucks, mine carts, and equipment litter the ground, and on-theme music is played through scratchy-sounding old-timey speakers. Virtually from the time you enter the queue, and undoubtedly from the time you enter the temple section of the queue, you are entering the story.

The other stand-out attraction to come out in recent years, which demonstrates what could be called the ‘Continuous Story’ principle, also utilized the tactic to such a masterful degree primarily because it was forced to. The Twilight Zone Tower of Terror – whisking passengers up in their “broken maintenance elevators” and then back down faster than the speed of gravity – is a phenomenal attraction, but, due to the nature of the ride, it came pre-packaged with a case of shortcomings: Only one ride vehicle can exist in the elevator shaft at any given time. Even with 3 elevator shafts operational, this means that only 3 cars can actually be experiencing the main part of the attraction at any given time.v That means a far longer line to get far fewer people on the ride than, say, Pirates of the Caribbean, or the Haunted Mansion. The inevitable solution is to make the queue feel like the part of the ride.

The open areas around the line itself, such as the lobby at the front of the Hollywood Tower Hotel, are jam-packed with references to the original Twilight Zone television show. In the lobby, Talking Tina, the child’s pull-string doll with a penchant for murder, sits on the couch. Other references include the golden thimble from “The After Hours” episode, a stop watch capable of stopping time (… forever), a typewriter that ‘practically writes by itself’ (… or literally), and Henry Bemis’s tragically post-apocalyptic shattering glasses from my favourite episode, “Time Enough At Last”.vi Even for non-Twilight Zone fans, the feeling of actually waiting in line is augmented, and the story started off, by being ushered into a library (by Hotel Bellhops) and observing a thunderstorm, until, suddenly, a ‘unique’ episode of the Twilight Zone starts, staring you, complete with a black-and-white television introduction from Rod Serling. Watching the television introduction, amidst the eerie thunderstorm scene, feels like part of the attraction, and starts the story far in advance of boarding the actual (and, as previously mentioned, scarce) ride vehicles. However, once you are ushered out of the library, you are again confronted by waiting in line – in a capacity that feels like waiting in line – as the queue continues in the Hollywood Tower Hotel’s boiler room.

While these 2 recent attractions certainly stand out as excellent examples of this applied principle, the absolute best example of starting the story in the line again resides in New Orleans Square – inside of the Haunted Mansion. Many of the show buildings of the enormous E-Ticket spectaculars that border the west side of Disneyland were placed outside of the park’s berm – Indiana Jones Adventure, Pirates of the Caribbean, Splash Mountain, and the Haunted Mansion are all cut into two pieces by the intersection of the Disneyland Railroad. To reconnect the attractions, Imagineers came up with some pretty fun stuff; the drop at the beginning of Pirates of the Caribbean, the long Indiana Jones queue, and the viewport for Disneyland Railroad guests to actually look in to Splash Mountain, for example. In the Haunted Mansion however, they took what was already one of the longest attractions in the park (and still is) and extended it.

Unlike Pirates of the Caribbean, which has its first show building inside of the boundaries of the park’s berm, and above ground, the Omnimover ‘Doom Buggies’ of the Haunted Mansion load and unload underground. Guests are delivered to their subterranean starting positions by the stretching portrait chamber – an elevator, rigged with special effects – which begins almost immediately inside of the Mansion’s facade. Before you enter the elevator, you are herded into a foyer, where you hear an introduction from your ‘Ghost Host’. Depending on how busy the ride is, you might stay in this chamber for several minutes, listening to the introduction, and waiting for one of the 2 stretching portrait elevators to make its way back up to entrance-level and start loading a fresh group of guests. The elevator ride lasts, from what I can tell by timing ride-throughs of the attraction on YouTube, approximately a minute and a half from when the doors open to load passengers to when they open again, once underground, to unload the passengers.vii The elevator delivers you to another, much smaller, section of queue – once again, intricately themed and laden with special effects, including busts of disembodied heads that seem to constantly be looking at you, windows showing a thunderstorm happening ‘outside’, and portraits that reveal their true, frightening undertones with each illuminating flash of lightning. The ghost host’s voice continues in this section, beckoning for volunteers to fill the one remaining slot at the mansion. This section of the queue, again depending on how busy the attraction is, can take around 5 minutes to walk through, before you are fully loaded into your ‘Doom Buggy’.

This all occurs before the 9-minute attraction actually begins.viii Not only is the story introduced in this last section of the queue, but the queue actually feels like part of the attraction. Despite the actual rideable circuit of the Omnimover system being only 9 minutes long, all of the YouTube ride-throughs that I watched in preparation for writing this chapter lasted 12 minutes or more – and all of them started not at the boarding platform of the ‘Doom Buggies’, but at the entrance to the mansion. The ride-through version of the soundtrack on the official Disneyland album lasts just under 14 minutes.ix I, and everyone else I’ve ever gone to the park with, considers the ride to start from the time you enter the Foyer and the voiceover starts. This is an amazing feat; proportionally to how busy the overall attraction is, this final themed section of the queue lasts (approximately) between 5 and 10 minutes (maybe more). Even on busy days, due to the monster-sized capacity of the Haunted Mansion, the wait time does not usually surpass 40 minutes, topping out at maybe an hour for special events. Factoring this in, this last themed section of the queue represents perhaps a quarter of the total time spent waiting in line, even when the attraction is busy. Considering that the attraction ride-time is 9 minutes, this themed queue section practically doubles the perceived run-time of the ride.

Originally, both Pirates of the Caribbean and the Haunted Mansion were intended to be walk-through attractions, so it seems very logical that this leap of starting the story (and, really, of starting the attraction in the queue) was made with these rides. Imagineers could simply take some of the effects and scenes planned for walk-through areas and put them in the ‘walk-through areas’ of the new rides: the queue. The effects that practically double the perceived run-time of the Haunted Mansion represent a great conceptual understanding and leap, and a great attention to detail, but are not very complex (…or comparatively expensive). Not a single animatronic is used in the themed queue section of the Haunted Mansion; the effects are accomplished with not much more than speakers, strobe lights, black-light paint, theatre scrim material, lighting tricks, and clever combinations thereof. The busts whose heads seem to follow you, for instance, are not ‘busts’ at all. The effect is achieved by having the image of the busts ‘carved out’ inversely in the wall, then lit to have the shadows that a normal 3-dimensional sculpture would have. When you move, your perspective in relation to the inset image changes, but since the lighting makes it look like a normal sculpture, your brain tricks you into thinking that the ‘busts’ are following you with their gaze; no expensive or complicated animatronics technology required whatsoever. The ingenious extending of the Mansion’s story into the line, resulting in truly an attraction which begins in the line, didn’t even represent much comparative additional expense.

While some of the attractions that best demonstrate the Continuous Story Principle are Imagineering’s recent endeavours, such as the aforementioned Indiana Jones Adventure and The Twilight Zone Tower of Terror, the lines of some of the most recent attractions have faltered in recent years – once again, in Paradise Pier. When I first rode one of the most recent additions to California Adventure, ‘The Little Mermaid ~ Ariel’s Undersea Adventure’, while I was impressed by the ride, I was throughly disappointed by the queue. As I eluded to in the first chapter, the inclusion of Ariel in Paradise Pier is a bit nonsensical. Paradise Pier isn’t built for sustainability like the original Walt-designed lands of Disneyland were; Paradise Pier is themed around a specific thing – a coastal amusement park from around the turn-of-the-century – and thus doesn’t lend itself easily to the inclusion of other Disney intellectual property. The transition from a coastal amusement park to an undersea, non-technological, mermaid story, set in the past, is jarring to say the least. The facade of the Little Mermaid attraction is themed alongside the architecture of Paradise Pier – not doing anything to ease this transition, but understandable; entirely switching architectural styles from turn-of-the-century to fairytale-inspired castle (in complete view of passerby) would be overly noticeable in and of itself. I was hoping that the queue would present a gradient – taking us from the amusement park to the world of Ariel in gradual steps much like the Indiana Jones queue. However, the queue does nothing to ease the jarring, out-of-place feeling. Instead, when you enter the facade for ‘The Little Mermaid ~ Ariel’s Undersea Adventure’, you are greeted by standard metal railings, snaking around to eventually connect with the Omnimover loading platform. The only transitional elements are the uneven window panes, which, while I assume were installed to give a sense of transitioning from Paradise Pier to a more whimsical, cartoon-style world, end up looking severely out of place – primarily because they aren’t accompanied by other matching architectural elements or fixtures. Additionally, the background of the loading platform displays a massive mural, showing The Little Mermaid’s story. This primarily looks ‘cheap’ and again, surrounded by the turn-of-the-century amusement park architecture and styling, out of place. Not only does the ride not introduce story elements into the queue – something which, considering the size of the ride and the almost constant lack of a high wait time, would be excusable – but the queue doesn’t even feel like part of the ride at all. The transition between the ‘outside world’ of Paradise Pier and the loading platform of ‘The Little Mermaid ~ Ariel’s Undersea Adventure’ is one of the most jarring disconnects I’ve ever seen in a Disney park.

While an Ariel-inspired Castle may have been out of place as an exterior present in Paradise Pier, perhaps a rocky cliff featuring a deep-sea cave would not. Guests could enter through the cave, which could be furnished with waterfalls and other simple but immersive special effects, which would become more and more themed to the story of The Little Mermaid as it led them away from elements still visible of Paradise Pier. Perhaps the Scuttle animatronic, present at the beginning of the Omnimover circuit of ‘The Little Mermaid ~ Ariel’s Undersea Adventure’, could be perched in a nest above the queue, interacting with the quests.

Because of the ride’s large capacity and continuous loading (thanks to the Omnimover system), the queue of ‘The Little Mermaid ~ Ariel’s Undersea Adventure’ doesn’t really have to add much to the ride experience; guests are almost always in line for the attraction for less than 15 minutes. The ride has no other major constraints which forced the Imagineers’ hands when devising the queue, such as the separation problem posed by the bisection of the Disneyland Railroad through Indiana Jones Adventure or the Haunted Mansion. The standard queue of ‘The Little Mermaid ~ Ariel’s Undersea Adventure’ is not much of a problem – mainly, it is a missed opportunity.

What is a problem, however, is the queue of ‘Toy Story Midway Mania!’, which does suffer constraints that call for an improved queue. The ride is one of the busiest in California Adventure, yet is one of the only E-Ticket calibre attractions in the park which does not feature Fast Pass kiosks. You cannot get a ticket to come back and ride ‘Toy Story Midway Mania!’ later; if you want to ride it, you have to wait in line. Given it’s popularity and capacity, the ride usually has a wait time of at least 30 minutes, even in not-so-busy conditions in the rest of the park. Yet the queue is the standard snaking lines of metal rails – leaving guests exposed in the sun for much of the line, nonetheless. Even the inside sections of the line lack air-conditioning. The inclusion of the attraction in Paradise Pier poses some of the disconnect problems highlighted by ‘The Little Mermaid ~ Ariel’s Undersea Adventure’ (although not to the same degree, since ‘Toy Story Midway Mania!’ is a midway-style game) which are not overcome by the queue; Why are the toys all of a sudden human height? How did they get here from Andy’s room? The queue is long, and feels long, with nothing to do, or even really look at.

There is one interactive feature in the queue: A person-sized Mr. Potato Head animatronic. Undoubtedly it was an expensive addition, as the animatronic is groundbreaking; it can remove it’s body parts, like a real Mr. Potato Head – the first animatronic to be able to do so. However, Mr. Potato Head suffers the same error to befall the Buzz Lightyear animatronic at Buzz Lightyear Astro Blasters in Disneyland: only a small section of the line can actually see the animatronic. Mr. Potato Head is situated near the front entry of the queue at ‘Toy Story Midway Mania!’, facing the boardwalk of Paradise Pier, leaving only a brief window for the people actually waiting in line to see (or interact with, as the figure responds to inputs via an operator) Mr. Potato Head.

This is likely to allow passerby on the Paradise Pier boardwalk to interact with the figure, but its inclusion may have caused the queue experience to be more unpleasant than it could have been otherwise:

The image in Fig. 6 shows the relatively small amount of encircling queue that can see the Mr. Potato Head animatronic at California’s version of ‘Toy Story Midway Mania!’. x

The cost of installing this one figure, however impressive and fun it may be, likely caused the rest of the queue to be skimped on. I’m an enormous fan of the effect, and of the groundbreaking effort from Walt Disney Imagineering to deliver the truly magical opportunity to interact with Mr. Potato Head, but it shouldn’t have come at the cost of creating one of the longest-feeling queues in the park. Considering the relatively few effects that cause the last 10 minutes of the Haunted Mansion’s queue to practically become a part of the ride, distributing these funds to a greater number of effects, and an overall more intricately themed queue, would have likely resulted in a far more improved queue experience, and helped with the transition between Paradise Pier and the inside of the ride, themed after Andy’s room.

The queue could have taken place mostly indoors, bringing guests into Andy’s room, very similar to the queue for Florida’s version of ‘Toy Story Midway Mania!’, located at Disney’s Hollywood Studios.xi This would offer a smoother transition between the boardwalk exterior and the show building of the ride, and would also offer ample opportunity for interactive elements. Animatronics of the toys – perhaps less complicated and costly than the Potato Head figure – could be placed central to the queue and set up the plot that led the toys to stage a midway game in Andy’s room. Moveable pieces and playable games could even be placed alongside the line, giving guests, particularly kids, something to do – much like the remodelled line to the Magic Kingdom’s Haunted Mansion.

It is critical to remember one of the final design lessons from the last expansions overseen by Walt Disney: the queue is part of the experience. At Disneyland, everything is part of the experience. The stories of the best attractions are not defined by lines, but gradients, which blur the space between the attraction’s rideable circuit and the themed area of the land it resides in; The attraction doesn’t have to start only when you board the ride vehicle.